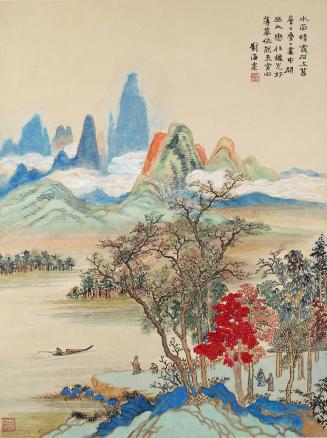

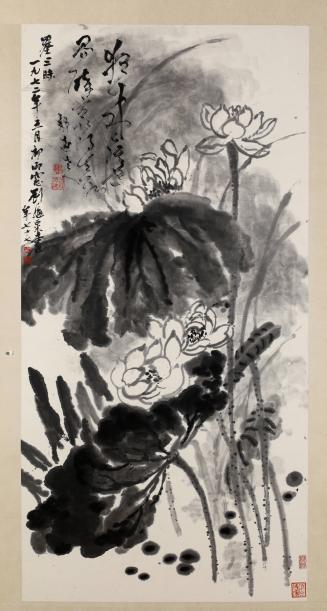

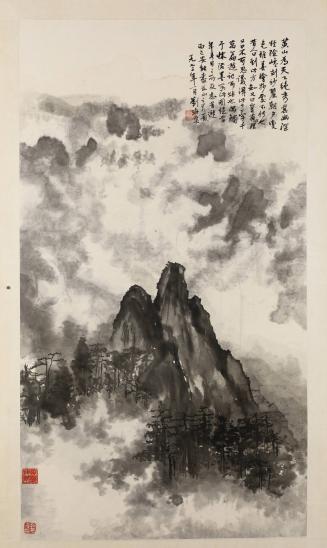

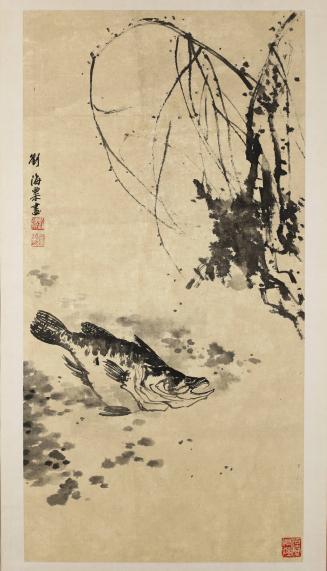

Liú Hǎisù 刘海粟 / 劉海粟

Liu Haisu (Liu Hai-Su; Liú Haǐsù 刘海粟 / 劉海粟; courtesy name Jìfāng季芳; sobriquet Hǎiwēng 海翁; 1896—1994), was originally named Liú Pán 刘槃 / 劉槃. He was born to a wealthy family in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province. His father, Liú Jiāfèng 劉家鳳, a well-educated man, in his youth joined the army of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom 太平天國 that was rebelling against the imperial government of the Qing dynasty. After the army was defeated, he returned home to run a family business. Liu’s mother, Hóng Shūyí 洪淑宜, was the granddaughter of Hóng Liàngjí 洪亮吉(1746—1809), a distinguished scholar and statesman during the Qianlong (1735—1796) and Jiaqing period (1796—1820) of the Qing Dynasty (1644—1912). At an early age, Liu started to study poetry under his mother and went to a private elementary school at the age of six while beginning to learn calligraphy and painting. Having noticed his artistic talent, his uncle Tú Jì 屠寄, a prominent scholar, provided him with books of model paintings and encouraged him to study and copy works by Yun Shouping (Yùn Shòupíng 恽寿平 / 惲壽平, 1633—1690) who was regarded as the founder of the Changzhou School of painting. In 1905, Liu entered Shengzheng Academy where he took Western-style courses in addition to traditional Chinese courses.

After his mother passed away in 1909, Liu went to Shanghai and learned basic skills of Western painting in a stage background painting studio founded by Zhōu Xiāng 周湘. Though he stayed in Shanghai for only six months due to his objection to Zhou’s teaching style, Liu got a chance to access and copy reproductions of European masterpieces there for the first time before returning to his hometown. In 1912, to escape from a forced marriage arranged by his father, Liu left again for Shanghai where he, together with Wu Shiguang (Wū Shǐguāng 烏始光) and Zhang Yuguang (Zhāng Yùguāng 張聿光), founded the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, the first art institute in modern China that aimed at combining the teaching of traditional Chinese art and Western art. Later in 1914, Liu advocated the use of nude models in his teaching, which had never happened before in China’s history of art education. Although Liu was considered as a pioneer in art education and got support from the intelligentsia for this groundbreaking but controversial advocacy, he was called “the traitor of the arts” by the conservatives. In 1918, he launched Meishu 美術, the first art journal in China. After initiating coeducation in the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts in 1919, Liu made his first visit to Japan to study art education there. In the same year, he founded the artist group Tianma Hui 天馬會 with other instructors in the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts. Upon invitation from Cai Yuanpei (Cài Yuánpéi 蔡元培, 1868—1940), the esteemed educator and president of Peking University, Liu went to Beijing in 1921 to give a speech at the university and held an exhibition there in the following year. He started to study calligraphy under Kang Youwei (Kāng Yǒuwéi 康有為, 1858—1927) in 1921, and at the same time, resumed his practice of Chinese painting under the influence of Chen Shizeng (Chén Shīzēng 陳師曾, 1876—1923) and Yao Hua (Yáo Huá 姚華, 1876—1930).

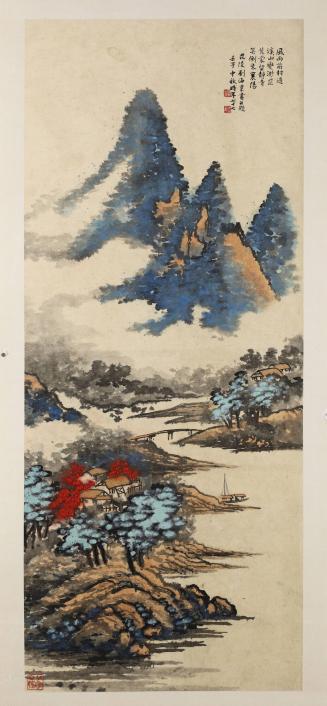

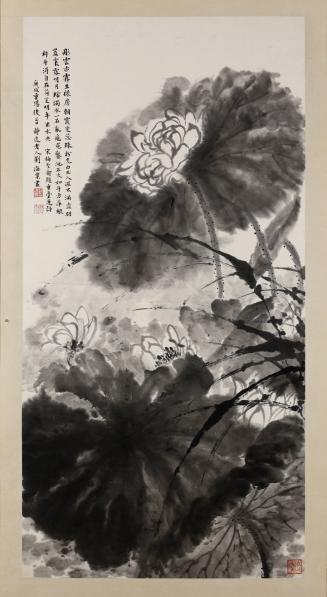

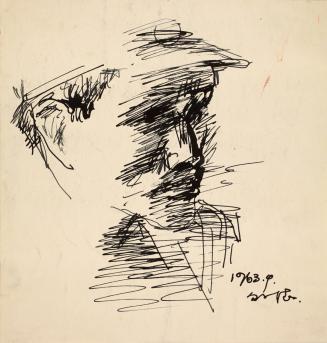

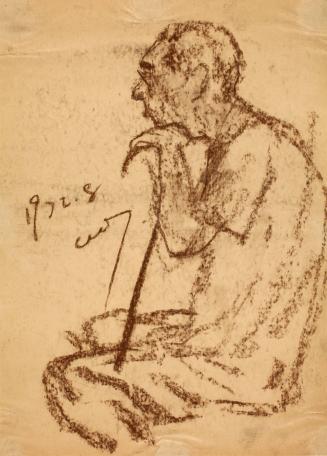

In 1927, in order to escape from political persecution, he again went to Japan, meeting with Japanese painters and holding a solo exhibition at the Asahi Shimbun Company in Tokyo. Returning to China after the arrest warrant against him had been revoked in 1928, Liu was then sent by the government to Europe in 1929 to study Western painting techniques as well as survey art education. During the three years Liu stayed in Europe, his works were selected into the Salon three times. In 1931, he was invited to give a speech on the “Six principles of Chinese paintings” of Xie He (Xiè Hè 謝赫, 479—502) at the Chinese Institute of Goethe University in Frankfurt. Liu made his second visit to Europe from 1933 to 1935 to help prepare an exhibition of modern Chinese paintings which was held at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin in 1934 and subsequently moved to the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1935. In 1952, Liu was appointed to be the first president of the Eastern China Institute of Arts (which later became Nanjing Arts University) where he, as both an artist and an educator, underscored personal expression as well as “spirit” in painting. Criticized as reactionaries during the Cultural Revolution, Liu and his family were oppressed harshly beginning in 1966 and did not receive vindication until 1972. Despite the political persecution, Liu kept exploring Chinese ink painting as well as oil painting during this period of time and created an innovative method of splashed-ink and splashed-paint, a method that combined the visual effect of oil paint with freehand brushwork as well as the spirit of traditional Chinese painting. This became one of Liu’s signature styles in his later landscape paintings which usually featured Huangshan 黄山 (“Yellow Mountain”), a place he was so fond of that he visited ten times from 1918 to 1988. In 1981, Liu became a visiting professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong. Throughout his nineties, Liu travelled to various places including Huangshan and the Grand Canyon to study nature and make sketches. He died in Shanghai in 1994.

Zimeng Xiang

Sources:

Liu Haisu Art Museum. “Sheng ping jie shao.” Accessed August 19, 2016.

http://www.lhs-arts.org/aboutlhs/lhs.html#a12.

Liu Haisu Art Museum. “Yi shu lun zhu.” Accessed August 19, 2016.

http://www.lhs-arts.org/aboutlhs/works.