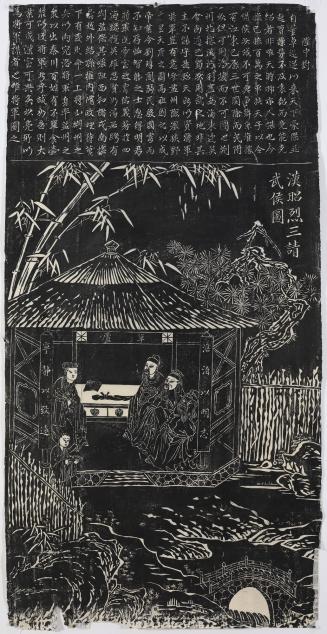

Auspicious Still Life

Artist/Maker

Chinese

Date18th century

MediumHanging scroll, ink and color on silk and paper

DimensionsOverall: 45 × 24 in. (114.3 × 61 cm)

Frame: 83 × 34 × 2 in. (210.8 × 86.4 × 5.1 cm)

Frame: 83 × 34 × 2 in. (210.8 × 86.4 × 5.1 cm)

Credit LineGift of Charles L. Freer

Object number1912.37

Status

Not on viewThough this may appear to be a random assemblage of items, each part of this still life has been carefully selected to be filled with auspicious symbols and visual puns. Below is an array of lucky objects: a vase of flowers, a string of amulets, an incense burner, symbolic fruits and plants, and a woman and child on a platform.

Known as a duānwǔ huàtí (端午畫題), or “Duānwǔ Festival Subject,” this type of work was displayed around the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, the date of the Duānwǔ Festival, which is also known in English as the Dragon Boat Festival or Double Fifth Festival. The modern interpretation of the festival's history relates to the poet and politician Qū Yuán 屈原 (c. 340 BCE – 278 BCE), a historical figure in the ancient kingdom of Chǔ 楚 who was forced into exile by a corrupt court. The Chǔ kingdom was conquered by the Qín state in their march to unify the country as the first empire. One version of Qū Yuán's story suggests that after learning of the fall of his kingdom, he committed suicide by walking into the Miluo River carrying a heavy stone. Villagers raced in boats to save him, and when they failed, they cast rice balls into the river to protect his body from being eaten by fish. This serves as an origin story for the dragon boat races and the sticky rice dumplings called zòngzi 粽子 still enjoyed today.

Aside from its origin story, the Duānwǔ Festival also became linked with beliefs about protection and well-being. Celebrated near the summer solstice, this time of year was traditionally seen as one of heightened danger from malevolent forces. To protect themselves, people turned to objects and images with protective or lucky symbolism such as this one. At the top are four Daoist talismans–magical diagrams believed to ward off evil. The woman and boy on the left symbolize wishes for a wife and son. The boy holds a ruyi scepter, an object that means "may everything go as you wish," traditionally given on important occasions. Below is a list of the other symbols in this painting and their meanings.

Joanne Kim (OC 2026)

SYMBOLISM IN AUSPICIOUS STILL LIFE

Top Register

•Daoist talismans ( fúlù 符箓): protective calligraphic spells, consecrated with a red seal.

•Zhōng Kuí 鍾馗: a popular deity who fights demons and evil forces. Images of him in red were believed to protect children from smallpox.

String of Amulets

•Bottle Gourd: On Duānwǔjié, upside down gourds absorbed evil vapors and were discarded at the end of the day. Bottle gourds on vines with roses symbolized Eternal Spring for Ten-thousand Generations (萬代長春), a play on the word in Chinese for vine and a name for roses.

•Loquat (pipa): The golden yellow color of these fruits symbolizes gold. The plant also embodies the four seasons: buds in autumn, blossoms in winter, fruits in spring, ripens in summer.

•Snakes: One of the “Five Poisons”, with toads, spiders, scorpions, and centipedes. Images of these poisonous creatures were believed to ward off evil.

•Cymbidium: a kind of orchid. The name in Chinese, lánsūn 蘭蓀 is a pun on the word sūn 孫 (grandson), and therefore a wish for male descendents.

Vase •Vase ( huāpíng 花瓶): is a pun on “peace” ( hépíng 和平).

•Peony and Poppy: May you be clothed in silk brocade and enjoy wealth and honor (衣錦富貴), a play on the names of the flowers in Chinese.

•Mugwort and Sweet Flag: Mugwort leaves look like hands, paired with Sweet Flag (below) with long, sword-shaped leaves; together they represent fighting off danger.

Left Platform

•Young woman and child: a wish for a wife and son, but also an image of the heroine Cáo É 曹娥 (AD 130–144), who perished trying to save her father from drowning during the Dragon Boat Festival.

•Mandarin Orange-shaped bag: held powdered herbs and spices to protect from pestilence.

•Scholar’s Rock and Pine: Both symbols of longevity.

•Rúyì 如意: The ( rúyì is the scepter held in the woman’s hand. It is a talisman, whose name means “May things go as you wish.”

Right Side •Lion: Protects against evil, although tigers appear more often in holiday symbolism. Lions traditionally look like long-haired dogs in Chinese art.

•Incense Burner

Below •Fruits: lucky fruits associated with the festival include cherries, loquats (which here look like yellow cherries), and lychees (which here look like big strawberries).

•Pomegranates: the many seeds were a wish for many children.

•Peaches: longevity, a reference to the magic peaches of immortality.

•Toad: One of the “Five Poisons”, with snakes, spiders, scorpions, and centipedes, used to ward off evil.

Thanks to Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art (2006) by Terese Tse Bartholomew for many of these interpretations.

ProvenanceCharles L. Freer [1854-1919], Detroit, MI; by gift 1912 to Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH; by transfer 1917 to Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OHExhibition History

Known as a duānwǔ huàtí (端午畫題), or “Duānwǔ Festival Subject,” this type of work was displayed around the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, the date of the Duānwǔ Festival, which is also known in English as the Dragon Boat Festival or Double Fifth Festival. The modern interpretation of the festival's history relates to the poet and politician Qū Yuán 屈原 (c. 340 BCE – 278 BCE), a historical figure in the ancient kingdom of Chǔ 楚 who was forced into exile by a corrupt court. The Chǔ kingdom was conquered by the Qín state in their march to unify the country as the first empire. One version of Qū Yuán's story suggests that after learning of the fall of his kingdom, he committed suicide by walking into the Miluo River carrying a heavy stone. Villagers raced in boats to save him, and when they failed, they cast rice balls into the river to protect his body from being eaten by fish. This serves as an origin story for the dragon boat races and the sticky rice dumplings called zòngzi 粽子 still enjoyed today.

Aside from its origin story, the Duānwǔ Festival also became linked with beliefs about protection and well-being. Celebrated near the summer solstice, this time of year was traditionally seen as one of heightened danger from malevolent forces. To protect themselves, people turned to objects and images with protective or lucky symbolism such as this one. At the top are four Daoist talismans–magical diagrams believed to ward off evil. The woman and boy on the left symbolize wishes for a wife and son. The boy holds a ruyi scepter, an object that means "may everything go as you wish," traditionally given on important occasions. Below is a list of the other symbols in this painting and their meanings.

Joanne Kim (OC 2026)

SYMBOLISM IN AUSPICIOUS STILL LIFE

Top Register

•Daoist talismans ( fúlù 符箓): protective calligraphic spells, consecrated with a red seal.

•Zhōng Kuí 鍾馗: a popular deity who fights demons and evil forces. Images of him in red were believed to protect children from smallpox.

String of Amulets

•Bottle Gourd: On Duānwǔjié, upside down gourds absorbed evil vapors and were discarded at the end of the day. Bottle gourds on vines with roses symbolized Eternal Spring for Ten-thousand Generations (萬代長春), a play on the word in Chinese for vine and a name for roses.

•Loquat (pipa): The golden yellow color of these fruits symbolizes gold. The plant also embodies the four seasons: buds in autumn, blossoms in winter, fruits in spring, ripens in summer.

•Snakes: One of the “Five Poisons”, with toads, spiders, scorpions, and centipedes. Images of these poisonous creatures were believed to ward off evil.

•Cymbidium: a kind of orchid. The name in Chinese, lánsūn 蘭蓀 is a pun on the word sūn 孫 (grandson), and therefore a wish for male descendents.

Vase •Vase ( huāpíng 花瓶): is a pun on “peace” ( hépíng 和平).

•Peony and Poppy: May you be clothed in silk brocade and enjoy wealth and honor (衣錦富貴), a play on the names of the flowers in Chinese.

•Mugwort and Sweet Flag: Mugwort leaves look like hands, paired with Sweet Flag (below) with long, sword-shaped leaves; together they represent fighting off danger.

Left Platform

•Young woman and child: a wish for a wife and son, but also an image of the heroine Cáo É 曹娥 (AD 130–144), who perished trying to save her father from drowning during the Dragon Boat Festival.

•Mandarin Orange-shaped bag: held powdered herbs and spices to protect from pestilence.

•Scholar’s Rock and Pine: Both symbols of longevity.

•Rúyì 如意: The ( rúyì is the scepter held in the woman’s hand. It is a talisman, whose name means “May things go as you wish.”

Right Side •Lion: Protects against evil, although tigers appear more often in holiday symbolism. Lions traditionally look like long-haired dogs in Chinese art.

•Incense Burner

Below •Fruits: lucky fruits associated with the festival include cherries, loquats (which here look like yellow cherries), and lychees (which here look like big strawberries).

•Pomegranates: the many seeds were a wish for many children.

•Peaches: longevity, a reference to the magic peaches of immortality.

•Toad: One of the “Five Poisons”, with snakes, spiders, scorpions, and centipedes, used to ward off evil.

Thanks to Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art (2006) by Terese Tse Bartholomew for many of these interpretations.

An Eclectic Ensemble: The History of the Asian Art Collection at Oberlin

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH (August 27, 1999 - August 30, 2000 )

Chinese Art: Culture and Context

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH (January 2, 2002 - June 2, 2002 )

The Enchantment of the Everyday: East Asian Decorative Arts from the Permanent Collection

- Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, OH (July 9, 2019 - September 3, 2021 )

Collections

- Asian

The AMAM continually researches its collection and updates its records with new findings.

We welcome additional information and suggestions for improvement. Please email us at AMAMcurator@oberlin.edu.

We welcome additional information and suggestions for improvement. Please email us at AMAMcurator@oberlin.edu.

first half 20th century

first half 20th century

early 19th century

18th–19th century

first half 20th century

first half 20th century

19th century